After I changed my mind about writing new JavaScript frameworks, I paused development on a new project, What the Framework (WTF). Here's why.

After I changed my mind about writing new JavaScript frameworks, I paused development on a new project, What the Framework (WTF). The project was intended to be a way to help people choose a JavaScript framework to use for their next project based on the features they needed from a framework, rather than opinion or the latest hype. During the project’s development, however, it became clear that in the exponentially changing technical landscape of 2022, the question of whether to specifically choose to build a Single-Page Application (SPA) or Multi-Page Application (MPA) was not as simple as it seemed.

It’s not all bad, though! Whilst deep in my research for the WTF project, I discovered some interesting historical information about Twitter tech and its development over time — and I’ve reached an interesting conclusion. Given that there’s a lot of talk about Twitter’s new ownership and where this might lead the platform right now, I thought it would be a good time to share my findings. But first, let’s take a look at what we mean by a SPA.

What is a SPA?

A SPA is a JavaScript application that, once loaded in the browser, updates the page view locally by modifying the DOM, rather than by navigating to a new page as an HTML response from the server. As a result, SPAs are able to persist parts of a page that don’t change between routes, such as login state or work in progress. Whilst there are certainly ways to maintain state without using a SPA, such as using session cookies or your own bespoke JavaScript, the SPA approach is often useful for front end developers who don’t want to venture into more back-endy territory. The core concept of SPAs is to make web pages feel like native device applications through faster page transitions. Examples of SPA frameworks include Next.js, Nuxt, SvelteKit, Remix, Gatsby, and React.

How can you tell if a website is a SPA?

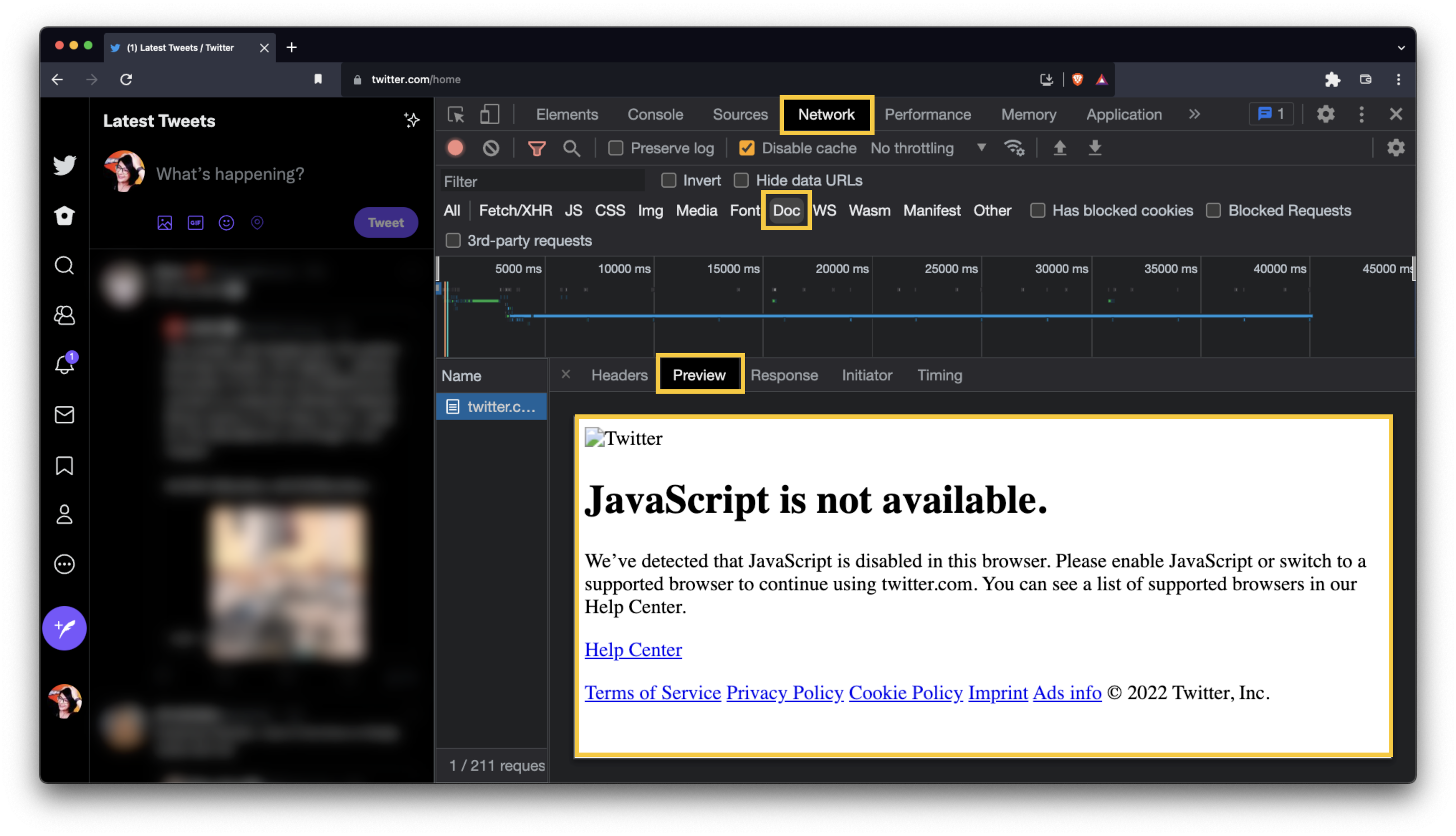

Open the network tab in your browser dev tools, filter by “Doc”, and refresh the page. You should see an HTML document loaded in.

If you’re viewing a SPA, you may either see a blank page in the network tab, or a message added by the app developers stating that the website needs in-browser JavaScript to work properly, such as in the case of Twitter.

What’s happening here, is that Twitter’s index.html is attempting to load the JavaScript application code required to rebuild and customise the HTML page locally. Without a browser environment with JavaScript enabled, JavaScript can’t run to update the HTML with new content, and the developers have kindly provided a fallback message to let you know.

In brief: MPA

In a MPA, HTML documents are rendered on a server, either at build-time in the case of pre-generated static sites, or at request time for server-side rendered pages. Every page in an MPA has its own file or route. When you navigate to a new page in an MPA, your browser requests a new page of HTML from the server, the server builds it and sends it back. Traditional MPA frameworks include Ruby on Rails, Python Django, PHP Laravel, WordPress, and static site builders like Eleventy or Jekyll. This is the way all websites worked until the late 2000s.

Was Twitter the original SPA?

The web community often regard Twitter as one of the first modern Single-Page Applications. During my research for WTF, I stumbled upon a blog post from Twitter published on 20 September 2010: The Tech Behind the New Twitter.com.

2010

In this post, Britt Selvitelle describes how Twitter “began implementing a new architecture almost entirely in JavaScript” alongside a redesign, and how one of the primary goals was “to make page navigation easier and faster” by providing “a rich web application that behaves like a traditional web site” — hello SPA! One of the most common concerns with SPAs (even to this day) is around supporting a wide range of search engine crawlers and conditions where JavaScript either failed, or was not able to run; if you can’t load JavaScript (i.e. you’re not in a browser environment), you can’t load a JavaScript application, and therefore you can’t load content that relies on JavaScript to understand what the page is about.

Encouragingly, Twitter made sure to consider this carefully in 2010 by building a Mustache-based rendering system that ran on both the server and client. (It’s a shame this didn’t persist into the present day!)

2012

Fast-forward to 2012 and Twitter released a new blog post announcing that to “take back control of [their] front-end performance”, they decided to move much of the rendering back to the server(!), given that the SPA-based approach “lacked support for various optimizations available only on the server.”

2013

There’s a bit of a gap in announcements between 2012 and 2017, but on 11 July 2013 (just nine days after React’s first public release) Twitter released Flight — “a lightweight, component-based JavaScript framework that maps behavior to DOM nodes” — which was used by Twitter at the time. The last release of Flight was in 2015 and it’s not under active development in 2022, but it’s interesting to note that whilst Flight was “organized around the existing DOM model” to “take advantage of native features”, React’s JSX abstraction ultimately gained more traction at the time. And React is still growing almost a decade later, as proved by the results of the latest Jamstack Community Survey:

React continued to grow to an almost unprecedented 71% share of developers, and Next.js rode that wave and is now used by 1 in every 2 developers.

2017

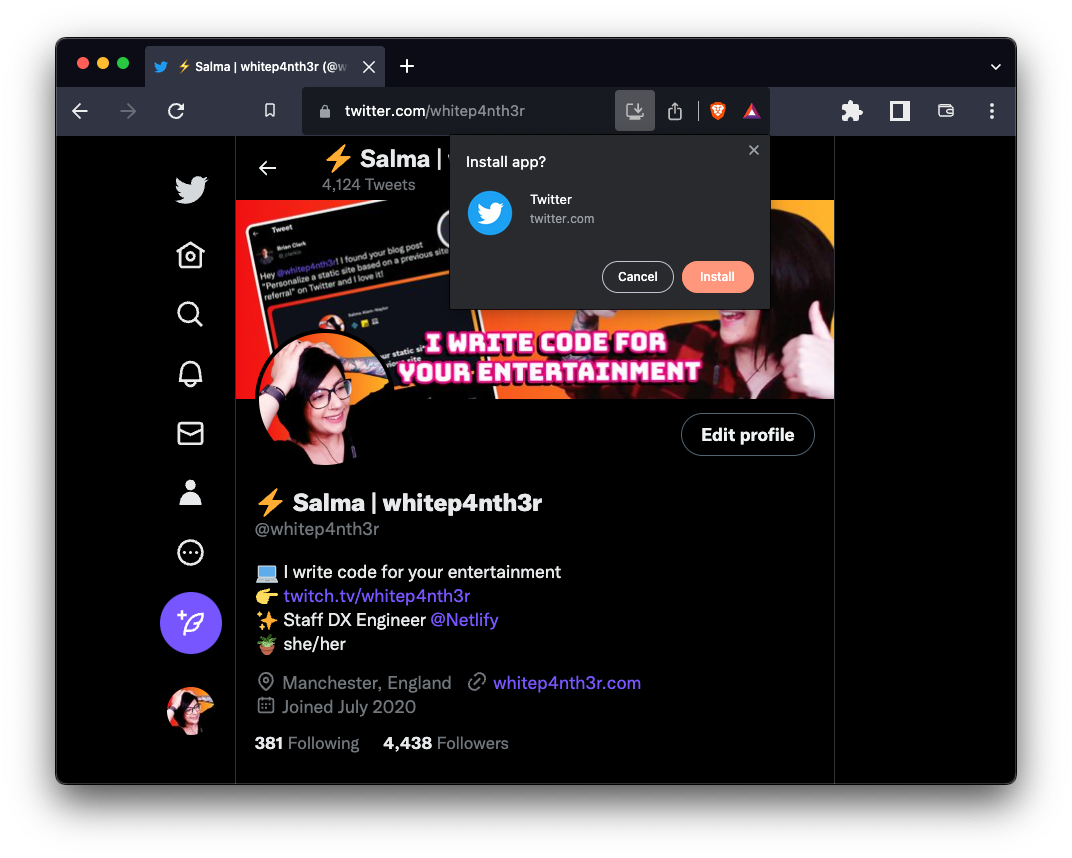

In further technical developments, in 2017 Twitter released Twitter Lite — a Progressive Web App (PWA). Progressive Web Apps go even further to replicate that native app-like experience of a SPA, by being “installable” on devices, supporting offline use and push notifications, whilst also being discoverable on the web and sharable via a URL. Initially aimed at improving the mobile Twitter experience by minimising data usage, loading quicker on slower connections and taking up less than 1MB of device space, you can still install Twitter on any device today, including desktop machines.

Twitter Lite was available at mobile.twitter.com — seemingly splitting the codebases for desktop and mobile devices at the time. Before hand-held devices became as powerful as they are today — and before CSS became more responsive by default with tools such as grid and clamp — this was the way things were done. All companies I worked at in the 2010s maintained separate desktop and mobile experiences, although we began merging the two experiences starting in 2017/2018.

It’s interesting to note that the web dev industry took so long to appreciate that the performance benefits and features of “mobile sites” are just as compelling on non-mobile devices, and that responsive web design and progressive enhancement could let us build the best experiences for users no matter where they are or what device they’re using.

2019

In 2019, Twitter followed suit and launched another new Twitter, this time with a “write once, run everywhere” philosophy, merging the desktop and mobile device experiences in code. This was further enhanced by only downloading visual elements to a user’s browser or device when they were needed, in order to prioritise data-saving on all devices.

And the cycle continues

Twitter tech has been on a journey — and so have many, many other codebases and products. Render everything on the server. Do everything in JavaScript in the browser. Do less in Javascript and move critical functionality to the server. Move all functionality back to the server. Use the platform. Write HTML. Abstract away the platform. Use {INSERT_NEW_SYNTAX_HERE}. And the cycle continues to the present day.

The initial question that prompted this post was: “Should we really be asking whether people should build a SPA or MPA?” I think the answer is yes… BUT — there’s more. I am fascinated by the technical journey that Twitter has been on over the last 12 years, and a lot of it mirrors the technical trends I have observed and built myself during my career as a front end developer and tech lead. But this journey also highlights the extra nuances to take into account when building a product, and ultimately when choosing the tech.

The technical choices you make don’t just rely on the features your product will need. These choices are also massively influenced by how people will use your product.

Who is your audience?

How fast is their internet connection?

What devices do they use?

Do they use more than one device frequently?

How do they actually use the product?

And what’s more, the options available to developers in 2022 are more varied than ever. Newer solutions to client-side JavaScript hydration, such as Islands Architecture are paving the way for more hybrid applications whilst prioritising shipping static HTML by default, and progressively enhancing the interactivity of the user experience in a more intentional way.

The changing landscape of hardware, internet connectivity, and social patterns — these all play a part in choosing the tech for our products. And this is likely to change as the world evolves around us. And so in conclusion: I’m not sure I can really build What the Framework effectively.

What do you think? Is What the Framework a lost cause? Let me know on Twitter (if it’s still around…)!

Salma Alam-Naylor

I'm a live streamer, software engineer, and developer educator. I help developers build cool stuff with blog posts, videos, live coding and open source projects.